Hypothermia occurs when your body loses heat faster than it produces it. The most common causes of hypothermia are exposure to cold-weather conditions or cold water. But prolonged exposure to any environment colder than your body can lead to hypothermia if you aren't dressed appropriately or can't control the conditions.

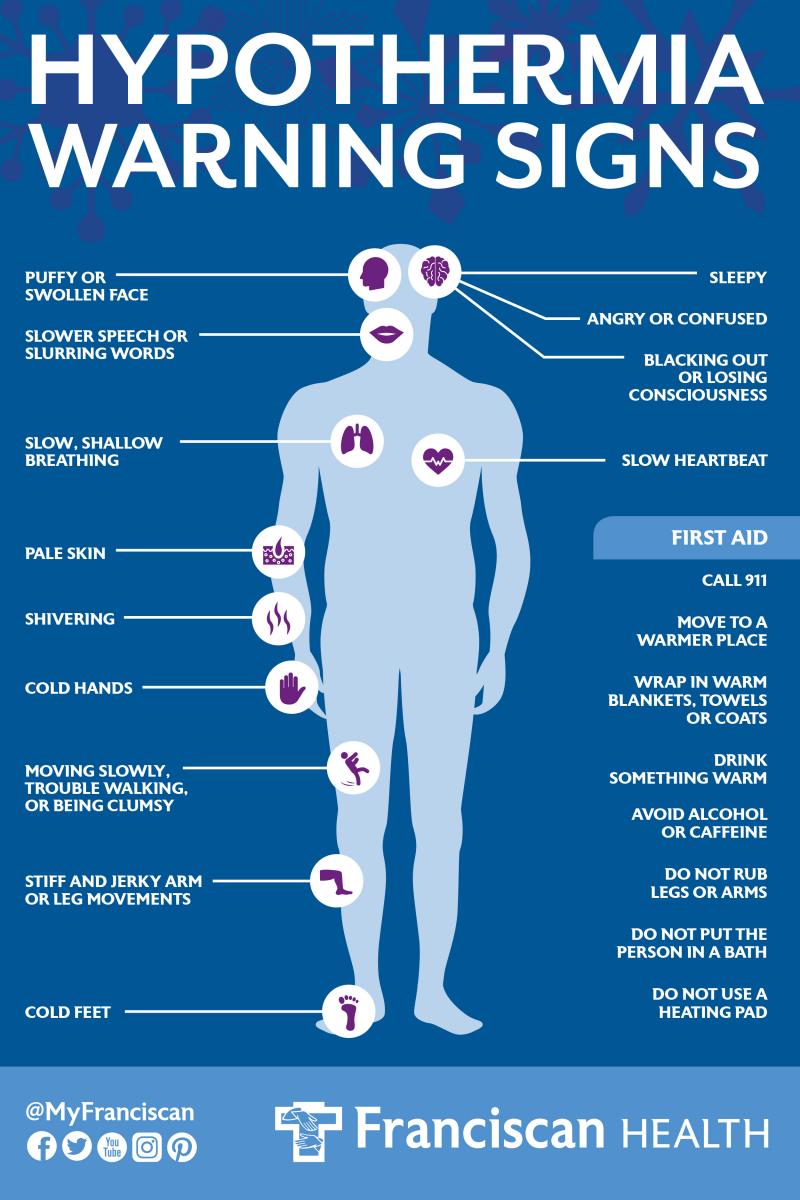

Shivering is likely the first thing you'll notice as the temperature starts to drop because it's your body's automatic defense against cold temperature — an attempt to warm itself. Signs and symptoms of hypothermia include:

Someone with hypothermia usually isn't aware of his or her condition because the symptoms often begin gradually. Also, the confused thinking associated with hypothermia prevents self-awareness. The confused thinking can also lead to risk-taking behavior.

Staying warm in cold weather Before you or your children step out into cold air, remember the advice that follows with the simple acronym COLD — cover, overexertion, layers, dry:

An avalanche (also called a snowslide) is an event that occurs when a cohesive slab of snow lying upon a weaker layer of snow fractures and slides down a steep slope. Avalanches are typically triggered in a starting zone from a mechanical failure in the snowpack (slab avalanche) when the forces of the snow exceed its strength but sometimes only with gradual widening (loose snow avalanche). After initiation, avalanches usually accelerate rapidly and grow in mass and volume as they entrain more snow.

For years, scientists have tried to measure these characteristics using infrared scanners or satellites, but these tools work best for large flat areas, such as with melting Arctic sea ice. Expensive laser or ultrasonic sensors on poles can accurately measure snow height, but these fragile devices are easily destroyed or shifted by snow movement on steep slopes. Plus it’s dangerous to jab probes directly into snowpacks in places where loose powder sits ready to plummet. So a team of researchers devised a hands-off way to monitor avalanche-prone peaks on Weissfluhjoch mountain near Davos, Switzerland. Over the course of two consecutive summers (2012 and 2013), they buried a small, upward-facing radar dish and a GPS antenna into the mountain dirt before the winter snows arrived. When the storms hit, they found that the radar could gauge snow height, while interference of the GPS signal provided a readout on liquid water content.

Yell and let go of ski poles and get out of your pack to make yourself lighter. Use "swimming" motions, thrusting upward to try to stay near the surface of the snow. When avalanches come to a stop and debris begins to pile up, the snow can set as hard as cement. Unless you are on the surface and your hands are free, it is almost impossible to dig yourself out. If you are fortunate enough to end up near the surface (or at least know which direction it is), try to stick out an arm or a leg so that rescuers can find you quickly. If you are in over your head (not near the surface), try to maintain an air pocket in front of your face using your hands and arms, punching into the snow. When an avalanche finally stops, you will have from one to three seconds before the snow sets. Many avalanche deaths are caused by suffocation, so creating an air space is one of the most critical things you can do. Also, take a deep breath to expand your chest and hold it; otherwise, you may not be able to breathe after the snow sets. To preserve air space, yell or make noise only when rescuers are near you. Snow is such a good insulator they probably will not hear you until they are practically on top of you.